Petroglyphs – Ancient Messages Etched in Stone

Rock art, or petroglyphs Mongolia, can be found primarily along the migration routes of ancient Mongolian nomads. These remarkable carvings are almost nonexistent in Europe, making them one of the most unique and awe-inspiring elements of Mongolian cultural heritage. Even within Asia, petroglyphs appear mainly in areas where Mongolians once traveled. For instance, a pair of American researchers spent seven to eight years studying petroglyphs on just two mountains in Bayan-Ölgii Province and published a four-volume book detailing their findings.

Messages from the Ancients

The petroglyphs preserved across the vast Mongolian landscape date back to the Old Stone Age and serve as messages from people who lived 3,000 to 5,000 years ago. These ancient carvings allow us to glimpse into Mongolia’s deep and rich history—like letters from the past engraved in stone.

The earliest petroglyphs depict wild animals, birds, and humans in simplistic forms, reflecting the skill level of those ancient artists. As time progressed, their artistic techniques improved. Later carvings not only captured wildlife but also detailed everyday life—hunting scenes, agriculture, domestication of animals, transportation using ox carts and chariots, and even intimate relationships between men and women. These depictions of carts and wagons, predecessors to modern vehicles, continue to captivate researchers today.

Unique to Mongolia’s Historic Routes

What makes these petroglyphs even more extraordinary is their exclusive presence along the historic paths taken by Mongolian nomads. These stone messages reveal a wealth of information about ancient life: the tools and technologies of different eras, dominant animal species of the time, the beginnings of domestication, early agricultural practices, the use of bows, plows, wheels, preparation for warfare, religious symbols, livestock branding, and even clues about where favorable living conditions once existed in Mongolia.

Found most abundantly within Mongolian territory, these petroglyphs are silent storytellers of the past. They represent a sophisticated form of communication—an artistic and thoughtful method by which ancient peoples ensured their stories would endure through the ages.

The Rock Art of Tsagaan Gol

On the eastern bank of the Tsagaan Gol (White River), located in Naran Soum of Govi-Altai Province, there are hundreds of petroglyphs etched into stone. These carvings were first discovered and studied by Mongolian archaeologist Ts. Dorjsuren, and later examined in greater depth by Soviet researchers V.V. Volkov and E.A. Novgorodova.

Tsagaan Gol is a mountain stream flowing through a narrow gorge, where the vertical rock walls are densely adorned with carvings. In addition to the gorge walls, smooth stones on the foothills of nearby mountains bear multiple rows of snake-like depictions. To the right of these serpentine motifs is a large depiction of a horse. Similar horses can also be seen carved on adjacent cliffs, with one particular composition depicting three horses interconnected in a unified scene. A nearby boulder to the northwest holds a worn image of a snake, now barely visible due to erosion.

On the western side of a rocky promontory, carvings from various historical periods are clustered together. Among them is a particularly ancient image of a horse, recognizable by its tucked-in belly. Other carvings in this area include a symbol resembling a person with a bow and arrow, possibly a tribal emblem; a man holding a long spear; deer; wild goats (ibex); elongated horses; two large animals joined at the head; a bird with outstretched wings; and a creature with a large mouth and drooping tail. In addition to these are numerous ambiguous figures and abstract lines whose meanings remain unclear.

Among the most intriguing petroglyphs at Tsagaan Gol are repeated images of seals or tamgas (tribal marks), archers in shooting posture, long-tailed horses, figures with horn-like head ornaments, and large animals with raised tails and massive curved horns. One notable scene depicts two men holding spears, dressed in traditional attire—tall hats, deels (robes), belts, and boots.

Beneath one of the rock panels is an intricate scene where five horses are shown pulling an unknown object. To the left, more horses and animals are linked together with what appears to be connecting lines or harnesses. Ancient depictions of carts are also present in this area. These carts are portrayed without animals pulling them, and their bodies are semi-circular with wheels bearing spokes in varying numbers. Scholars have noted striking similarities between these images and cart depictions found in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and even Scandinavia.

The Rock Art of Jargalant Mountain

At Jargalant Mountain, located in Tünel Soum of Khövsgöl Province, there once existed a significant collection of petroglyphs carved into stone. Unfortunately, most of these artworks have been lost due to quarrying activities for construction materials.

A notable remaining example was documented in 1997 by researchers G. Gongorjav and G. Enkhbat, who captured the image on photographic film. This surviving carving is found on an upright rock slab about the size of a traditional chest and depicts a stylized deer with multiple-branched antlers, a long, slender snout, and a sharply pointed, high-raised back.

The antlers are etched with a consistent, ornamental rhythm, giving them a decorative appearance akin to traditional Mongolian patterns. Based on its stylistic features, especially the idealized rendering and motif, the image is believed to date back to the Bronze Age.

The Rock Art of Sevrey Mountain

In 1997, researchers G. Gongorjav and G. Enkhbat discovered a significant collection of petroglyphs carved in shallow relief on the rocks at the foot of Sevrey Mountain, located in Sevrey Soum of Ömnögovi Province, approximately 15 kilometers from the soum center.

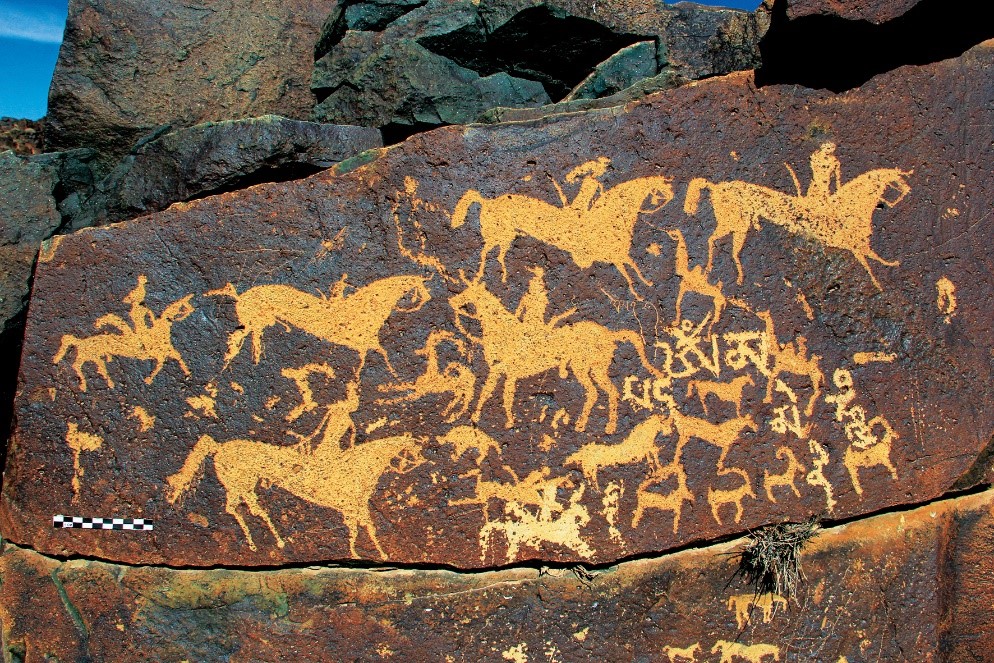

Among the carvings are depictions of three mounted warriors equipped with bows—locally referred to as the “Three Heroes”—accompanied by images of ibex, a dog-like animal, horses, a lone rider, gazelles (without horns), humans, fish-like figures, and numerous stamp-like symbols. One of the most striking scenes is that of mounted hunters pursuing wild ibex.

In this composition, four horsemen are shown chasing five ibex with magnificent curved horns and distinctive tails. All hunters are armed with bows, which are of a simple form—likely dating from the Bronze Age, prior to the invention of the composite bow. The horses are portrayed with realistically forward-pointing ears, elongated tails flowing backward, and long necks held high in a dynamic posture.

The stylistic features of the bows and the overall composition suggest that these carvings date back to the Bronze Age and provide fascinating insight into the hunting practices and artistic expression of ancient nomads.

The Rock Art of Ar Tsokhiot

Located approximately 10 kilometers southwest of the center of Züünbayan-Ulaan Soum in Övörkhangai Province lies a series of low hills situated in a long valley, known as Ar Tsokhiot. The area is dotted with numerous ancient burial mounds and stone circles (khirigsuurs). On the rocky slopes of a nearby hill called “Amitant” (literally meaning “With Animals”), a variety of wild animals were carved in shallow relief. Although many of the carvings have become weathered and faded over time, they remain a remarkable testament to ancient rock art.

A total of 235 individual figures have been recorded across 65 rock surfaces in this area. The majority of the images depict wild sheep (argali) and ibex. Other animals represented include moose, deer, wolves, horses, lynx, boars, dogs, oxen, snow leopards, camels, as well as human figures, abstract marks, and stamp-like symbols. Notably, there is also an image resembling a reindeer, created by outlining its body and leaving the interior uncarved to retain the natural color of the rock.

The deer and moose are often depicted in a realistic side profile, capturing anatomical features with notable accuracy.

Three distinct techniques of rock carving are evident in the petroglyphs of Ar Tsokhiot:

- Full Surface Pecking – where the entire body of the animal is recessed into the rock;

- Contour Carving – where only the outline is pecked and the interior left uncarved, using the rock’s natural surface tone to suggest the body;

- Internal Detailing – where the interior surface is crosshatched with fine lines to represent internal bones or organs, showing an early attempt at anatomical illustration.

These varying styles reflect a complex and sophisticated artistic approach, offering valuable insight into the visual culture and symbolic world of Mongolia’s ancient inhabitants.

The Rock Art of Baga Kharganat

In the territory of Tsetserleg Soum, Khövsgöl Province, a notable rock art panel was discovered northeast of the Baga Kharganat herder settlement, approximately 40 kilometers from the soum center. The carvings are found on a small rock surface measuring roughly 60 x 20 x 20 cm. No other petroglyphs have been identified on the surrounding rocks, making this an isolated yet intriguing site.

On the sun-facing (southern) side of the rock’s western face, one can observe the faint outline of three animals, including a dog with its tail raised. More prominently, on the right side of the rock are depictions of nine horses—eight large and one smaller figure that appears to be a foal. These horse figures are detailed with clear anatomical features, including gender and the mane.

Notably, behind the third horse from the top—which is carved with particular depth and robustness—there is a clearly defined image of a man. He is shown wearing a long traditional robe and boots, equipped with a bow, arrows, and a quiver, all carved in relatively large and distinct proportions.

This petroglyph harmoniously arranges a herder, his group of horses, and a dog within a very limited space, using a naturalistic style. It offers a vivid portrayal of pastoral life and implies a time when humans had fully adopted animal husbandry and mastered the bow and arrow. Based on stylistic and thematic elements, the artwork is likely attributable to the period just prior to the Bronze Age.

The Rock Art of Shovgor Zaraa

Located 26 kilometers southeast of the center of Buregkhangai Soum, Bulgan Province, the site known as Shovgor Zaraa lies in the fore-valley of Ikh Dulaan Mountain, just south of two small hills named Övögönt and Üüdent. On a small cliff on the eastern slope of this headland, a collection of ancient petroglyphs has been carved into the rock using pecking and engraving techniques.

The images include a variety of animals—some faded with time—such as long-tailed creatures, what appear to be camels lying down, horses, goats, and dogs, arranged vertically from top to bottom. One notable composition features a tree- or branch-like motif placed between a camel and another animal. Among the carvings, a distinctive square-topped ongin stamp (a traditional emblem) is shown with a cross-shaped base beneath it.

In another section, two reindeer or elk are depicted walking eastward, though the head of the leading animal has been eroded.

A separate grouping contains five animal figures, including a bull drawn with two narrow horns. Interestingly, there are carved depressions—one wide horizontal notch above its back and a thinner one below its belly—suggesting a human figure riding the animal, depicted in a highly stylized form.

Numerous symbols resembling seals or stamps are scattered among the rock art, including an oval mark with two long vertical lines that clearly resembles a tamga (tribal mark). While some human and animal figures are rudimentary in style, one depiction of a mounted rider is particularly striking.

Based on stylistic characteristics and subject matter, the petroglyphs of Shovgor Zaraa are attributed to the Early Iron Age, approximately 3000–1000 BCE.

The Rock Art of Urtyn Gol

Located in Khürkh Mountain within the territory of Nomgon Soum, Ömnögovi Province, the Urtyn Gol area is one of Mongolia’s richest sites of ancient petroglyphs. These rock carvings depict a wide range of scenes from ancient life—wild animals, hunting, pastoralism, and moments from human daily life and struggles. As a representative example, one notable granite rock face lies near the Urtyn Recreation Area, about 80 kilometers from the soum center.

On the slope of this granite boulder, there are carvings of a robust animal resembling a bull, a depiction of a man and woman in a sexual posture, and nearby, an ibex turning its head backward. Below these, the most intriguing images are large and deeply carved round faces enclosed within circles—one showing a figure with what appear to be glasses, spiky hair, and bared teeth. These eerie, exaggerated facial features evoke the masks or spiritual effigies of ancient shamans, resembling totemic deities or insect-like spirits from prehistoric mythology.

Another section of the same rock features three overlapping circular carvings containing stylized animal figures, a goat or ibex-like creature, and a horse with a large head, arched back, short legs, and a stubby tail. The composition and artistic style of these carvings suggest that they were created in various periods—not all at once—ranging from the Neolithic era to early phases of spiritual development rooted in shamanistic belief systems.

The diversity in subjects and techniques at Urtyn Gol clearly indicates a long continuum of symbolic and ritualistic expression spanning several epochs of Mongolia’s prehistoric past.

The Rock Paintings of Gachuurt Valley

Located approximately 25 kilometers east of central Ulaanbaatar, the red ochre rock paintings of Gachuurt Valley were first discovered and published in 1960 by the Russian archaeologist A.P. Okladnikov. These ancient pictographs are found on the eastern-facing cliffs on the western bank of the Gachuurt River and are considered a remarkable example of Bronze Age rock art in Mongolia.

Panel I

At the far western edge of the cliff, on a smooth rock surface, several motifs are depicted. These include a circular frame with dotted markings inside, a small circle divided into four quadrants by two intersecting lines, and a square enclosure filled with dot patterns. Below these are two human figures walking dogs. Further down to the left, three human figures and three dots are carved at some distance from the main composition.

Panel II

On the central flat surface of the rock, at the uppermost section, two humans are shown each leading a horse along parallel paths. Near one of the individuals, three dots are depicted. Below the path, two additional horses, three people, and two flying eagles are engraved.

Panel III

Lower down in the center of the cliff, another large flat rock contains depictions of a flying eagle above a solitary human figure. Beneath this, three rectangular enclosures are filled with rows of dots; within two of these, groups of four people each are shown standing hand in hand. Between the three enclosures, five people are again shown holding hands, and to the left of the enclosures, four more figures appear hand in hand. Below them, three additional individuals are similarly depicted.

Panel IV

To the left of the previous panels, within another rectangular enclosure, five people are shown in pairs or trios holding hands, along with a single horse. Adjacent to this are two more human figures, and beneath them, another person and several circular dot markings are portrayed.

Panel V

At the far eastern edge of the cliff, two people with their right arms raised face two horses. Nearby, birds are shown either sitting or in flight. Below them, two individuals are standing hand in hand on a narrow wavy line, with another person depicted below this scene.

Significance and Chronology

What distinguishes the Gachuurt Valley rock paintings from other red ochre pictographs across Mongolia is the abundance of horse and bird imagery, as well as the distinctive portrayal of human figures either raising or spreading their arms—often shown interacting with or leading horses. Notably, this site features what may be the only known red ochre depiction of a human leading a dog.

These stylized and somewhat schematic pictographs are generally attributed to the Bronze Age, based on both their artistic conventions and thematic content.