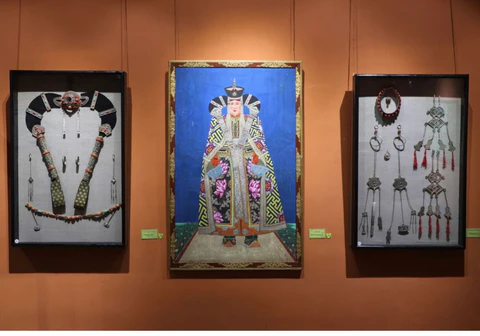

Headpieces

When a Mongolian woman got married, she would braid her hair into two plaits and adorn herself according to the customs of her region. In Central Khalkha, married women styled their hair by puffing it outwards into a circular shape, placing a silver clasp in the middle of the hair and an oval-shaped pin at the base. They would also wear a silver headpiece inlaid with precious stones that extended down to the forehead, over which a hat was worn.

This head ornament, called an oroivch, could signify a woman’s social status. If the crown of the oroivch was open, it indicated a commoner; if it was fully closed and decorated with khorol patterns (a sacred symbol), it indicated nobility or royal lineage.

Each side of the flared hairstyle was typically decorated with 6 to 8 silver clasps, with an oval clasp placed at the junction where the hair was inserted into a silver hair case called a tuiv. The tuiv was a hair clip that held the ends of the braids, symbolizing that the woman was married. Women concealed the ends of their hair in a velvet or silk hair pouch attached to the tuiv, ensuring their hair tips were never left exposed.

From the headpiece, sanchig ornaments would dangle down both cheeks. These side pendants were made of 3, 5, 7, or 9 strands of coral or pearl, representing both beauty and status.

Khalkha women also wore a breast pendant called an engeeriin guu, a sacred object worn at the chest. The string was crafted from silver and often decorated with mantras or precious stones. Only women of noble heritage were permitted to wear these.

Ear ornaments known as süikh were worn, typically shaped like the khorol symbol or fish, signifying the woman’s married status. Rings came in various styles and materials such as gold, silver, and steel—ranging from simple bands to engraved or gem-set designs. Bracelets were made of gold, silver, or copper and were either plain or intricately adorned with decorative patterns and stones. Altogether, the jewelry of a Khalkha woman could weigh between 5 to 6 kilograms.

In Western Mongolia, women also braided their hair into two plaits, which were placed in a black velvet hair pouch decorated with silk and allowed to hang down the chest. The ends of the braids were decorated with ornaments known as tokhig.

Women in Eastern Mongolia used elaborate hair decorations such as jeweled clasps, tatvuurga (hair bands), and magnaiwach (forehead bands), often made with precious stones.

Waist Ornament – Bel:

One of the most distinctive ornaments worn by Mongolian women is the bel, a circular pendant suspended from each hip. A Khalkha woman’s bel would often feature a central coral inlay with a spiral design, and five-colored scarves were hung from it. From the left-side bel, a snuff bottle and tobacco pouch were suspended.

On the right side, a set of items known as the five mischiefs (tavan savaagüi) were hung. Among Western Mongol tribes, this included a pouch, sewing tools, ear pick, nail cleaner, and toothpick. In Khalkha tradition, the five mischiefs included an ear pick, tongue scraper, nail cleaner, eyebrow trimmer, and toothpick.

The five-colored scarves symbolized many things: the red rising sun, joy and happiness, the vast blue sky, fresh rivers, and the earth itself. They also represented the blessings and virtues stored in a woman’s waist, symbolizing her role as the bearer of prosperity and well-being.

These scarves served practical purposes too, such as wiping hands, cleaning utensils, or use during milking. As a woman walked gracefully, the movement of these scarves created a gentle fluttering motion, expressing the softness and elegance of feminine poise.

Traditional Pearl Ornaments Worn by Mongolian Women

“There is a saying: ‘Beautiful hair enhances a beautiful appearance.’ Hair plays an important role in highlighting a person’s look. But how should one adorn the hair — particularly the traditional braid of Mongolian women? This question has long had its own unique answer. One such answer lies in the pearl combs and hairpieces worn by Mongolian women. These accessories, rich in symbolism and artistry, are a distinct category of traditional head ornaments.

Throughout history, combs made of wood, iron, or silver were crafted for grooming hair. Nowadays, plastic combs have become common. However, among Mongolian women, special combs for styling and adorning braids hold significant cultural value. This gave rise to the term “pearl comb.” The pearl comb is typically crescent-shaped, designed to fit the curvature of the head and extend from temple to temple.

These combs were traditionally made with a base of pure silver, gilded with gold, and decorated with pearls. The structural base consists of two main parts: the totgo — pieces placed above each temple, often shaped with traditional patterns — and the nuruun, a central bridge that connects the two. At the center of both the totgo and nuruun sits a gemstone, most often black onyx, while the rest of the surface is densely covered with pearls. The nuruun typically features 3 to 5 rows of pearls, depending on its size, and the totgo sections follow a similar design.

In addition to the comb, a hairpin or clasp (daruulgа) is made in the same style. Women with long hair attach this ornament to the roots or ends of their braids.

Pearl adornments were not only used in the hair. Mongolian women also wore pearl pendants on their chest, known as engeriin zuult (bosom ornaments). These pendants had silver bases, gilded in gold, and decorated with pearls. Such adornments were worn regardless of age, showcasing their cultural versatility. Historical sources even mention that the Queen of the Bogd Khan wore pearl-embellished shoes. It is clear that pearls have been cherished among Mongolians as both ornament and cultural symbol.

But what exactly are these pearls that became embedded in the culture and beauty of Mongolian women?

To answer this, let’s explore the nature of pearls.

Pearls are born in the warm waters of the ocean, forming inside mollusks and encased in a nacreous shell. Their beauty is unmatched — luminous, iridescent, and delicate. The term “mother of pearl” (or perlamutr, of German origin) refers to the origin of this captivating substance. The more one gazes upon a pearl, the more one feels its elegance. And no wonder — a pearl is a living entity, fading and reviving, shining with life.

Legend has it that Cleopatra dissolved a pearl in vinegar and drank it to prove her devotion to Mark Antony and to promote his health. Pearls, it seems, were not exclusively worn by women; even the robes of Indian maharajas were adorned with kilograms of pearls.

Pearls are classified by their origin: saltwater or freshwater, and by their formation: natural or cultured. Natural pearl harvesting is rare today, as it requires killing thousands of oysters to find a single true pearl. For this reason, people now prefer to culture pearls — a process almost identical to nature, except humans initiate it by inserting an irritant into the oyster.

A pearl takes between 2 to 7 years to form.

The history of cultured pearls is closely tied to the Japanese innovator Kokichi Mikimoto, whose technique caused a stir: by inserting grains of sand into oysters, he simulated natural irritation, causing pearls to form. In essence, a pearl is a mollusk’s “illness.” The oyster secretes nacreous layers over a foreign object to protect itself, eventually forming a pearl.

Modern science has revealed that pearls are the result of a biological defense mechanism. Waves carry sand and small particles into oysters, prompting them to layer protective nacre. A pearl is composed of 90% calcium carbonate, 5% water, and 5% conchiolin — an organic compound acting as a cementing agent. Interestingly, pearls can also form inside coconuts — a mystery still unsolved by scientists. Coconut pearls are larger than oyster pearls and are believed to possess healing properties. In some Asian countries, powdered pearl is even sold in pharmacies.